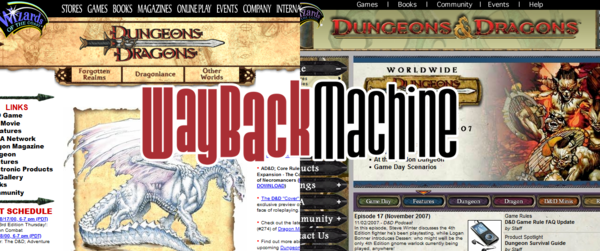

Wizards of the Coast - Dungeons & Dragons

Posted by palabomeno on Mar 24, 2021

If you are familiar with tabletop role playing games, you know Dungeons & Dragons. There’s a quote I like from the late, great Terry Pratchett, regarding J.R.R. Tolkien’s influence on the world of fantasy:

J.R.R. Tolkien has become a sort of mountain, appearing in all subsequent fantasy in the way that Mt. Fuji appears so often in Japanese prints. Sometimes it’s big and up close. Sometimes it’s a shape on the horizon. Sometimes it’s not there at all, which means that the artist either has made a deliberate decision against the mountain, which is interesting in itself, or is in fact standing on Mt. Fuji.

Dungeons and Dragons is like this in the world of tabletop gaming. If you’re making a TTRPG, you need to know where you stand on being compared to D&D. Will you try to differentiate yourself with interesting mechanics, a new setting, or will you try to learn from the game that invented tabletop roleplay? Like painting a scene of Japan without Fuji, it’s hard to not have D&D in the background somewhere, making its presence be known in the way you handled stats and skills, the shape of the dice you use, or even the deep, deep roots of your game’s concept.

What do you do when you are Mt. Fuji, though? How does the mountain learn to grow and change itself when the time comes to? What influences could Dungeons and Dragons itself draw from in the late 90s, the waning days of the Second Edition and the beginning of the Third?

Dungeons and Dragons Third Edition was a turning point for the game. It was D&D’s attempt to re-capture lightning in a bottle, to relive the heady days of its 80s fame, and make a Dungeons and Dragons game that was truly worthy of the name. It was… well, it certainly was a new edition of Dungeons and Dragons, that much can be said.

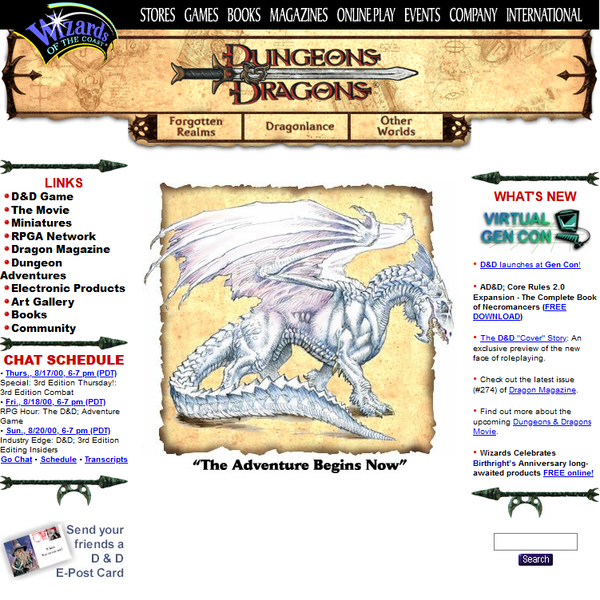

August 15th, 2000

D&D was in a bad, bad place in the 90s. TSR, the company founded by Gary Gygax himself, had been run into the ground by mismanagement. Gygax had left the company in the late 80s and Lorraine Williams had come into control, and she was terrible at managing the business. TSR had fallen behind both Games Workshop (maker of Warhammer) and Wizards of the Coast (makers of Magic: the Gathering) in sales. Newer, more interesting indie games like Vampire: the Masquerade sliced off huge chunks of the market with players interested in more story-driven, emotional games, and the rise of the internet fostered a burgeoning indie game scene with truly transgressive oddball games like Puppetland and HōL. Tabletop games were as big as ever, but D&D was falling behind.

D&D by this point had become an unbalanced, overcomplicated mess that was writing checks it could no longer cash. Sales were good, but TSR was spending much, much more than it could bring in. Attempts to cash in on trends manifested in the collectible Dragon Dice game, which was popular, but cost more to produce than it was bringing in. In 1997, facing no alternative, Williams sold TSR and the D&D brand to Wizards of the Coast - and Wizards was bought out by Hasbro a scant three years later!

D&D needed an overhaul. The second edition had lasted a staggering ten years, and was a bloated mess of mechanics, tables, incompatible settings, and just plain broken concepts. It was even still using the name of “Advanced Dungeons & Dragons” even though the basic game had been discontinued years ago! The website depicted above is from August of 2000, mere months before the release of Third Edition. You can see a “D&D launches at Gen Con!” link at the top of the right sidebar, which links to an article about pre-release content displayed at that year’s Gen Con, the convention for all things tabletop gaming.

So, what was Third Edition going to change? The most important difference was the new d20 System. In Second Edition, virtually any dice roll required a look at a chart to understand if you had passed or not. The “To Hit Armor Class Zero”, or THAC0 system, simplified this somewhat but not enough. Players would get confused by the arithmetic involved, especially when negative numbers get involved! In Third Edition, all of this was swept away and replaced with one simple principle. The Dungeon Masters sets a “Difficulty Class” number for how hard a challenge is - for example, an “average” challenge would have a Difficulty Class of 10. The player then rolls a d20 a “Skill Check”, adds any relevant modifiers (for example, skills in climbing, swimming, or plain raw charisma) and compares the final number to the DC. If it’s more, the player succeeds. If less, they fail.

This sounds dead simple, doesn’t it? It’s a far cry from having to reference tables in a book, switching between different kinds of dice, and not always knowing if you need to roll above or under a certain value to pass your roll. Third Edition promised to be a radical overhaul of everything D&D, something that would keep the old fans hooked while expanding the pool to all kinds of newcomers. But as always, the best laid plans of mice and men go aft agley.

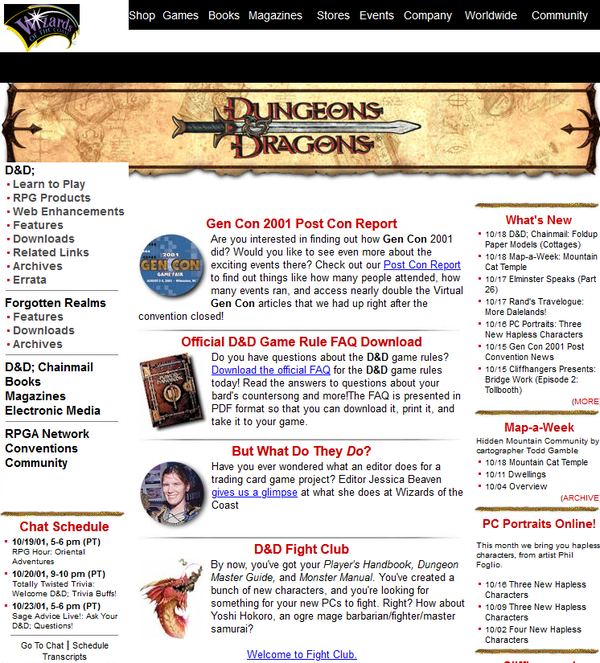

October 19th, 2001

Third Edition was welcomed with open arms, if without open minds. Sure, the old guard grumbled and complained that they didn’t have their oddball mechanics any more - any race can be any class! Gone was the race-as-class paradigm! There was no limit on how high certain classes could level! - but it was clear Third Edition was hitting D&D’s goals. Which can only mean one thing: bring on the splatbooks!

What is a splatbook, you ask? These are the books for content outside of the core rules - new settings, new classes, new monsters, all the stuff you want to bulk out your adventures into something truly unique! This, may we add, is the kind of thing that caused Second Edition to become overwhelming - we’ll get back to that later. The splatbook featured on this page is… Oriental Adventures, the modernization of one of D&D’s most racist books. Yeah, Third Edition tried to fix things a bit more on the mechanical side and wasn’t thinking too much about the social side, huh?

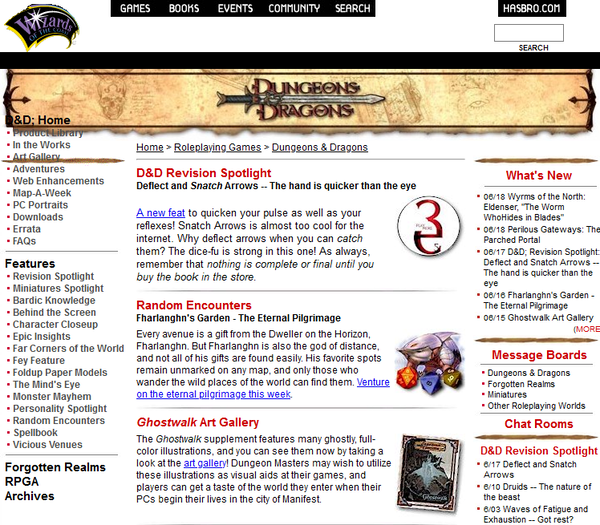

June 18th, 2003

Although Third Edition was supposed to fix all the problems with D&D, you guessed it, it had a lot of problems of its own. It was mostly fiddly bits - the way certain skills and feats, works, a few spells needed re-doing, some classes were grossly underpowered and needed a buff, things like that. So, what could be done? Just wait until a brand new edition after a decade or so?

No, Wizards had learned, and they were going to put their knowledge into action. They released Dungeons and Dragons 3.5 Edition, a minor overhaul that gave the Third Edition a good spit-polish and tuning-up. Was this just a plot to sell new books to people who already owned the core three? Probably not, but it did help sales that peoples’ books suddenly needed replacing.

With the release of 3.5 Edition, Dungeons and Dragons hit a new high. The changes were widely acclaimed by most players. They weren’t perfect, but they patched over some of the most obvious holes, like the completely unplayable Ranger class. Was D&D finally good again?

September 27th, 2004

No, not really. But hey, check out this new website design! And look at what just came out: Eberron!

In 2002, Wizards of the Coast held the Fantasy Setting Search, a competition for RPG writers across the world to submit their ideas to become D&D’s next big splatbook setting. Many people entered, but only Keith Baker’s Eberron won. Eberron was a version of D&D that truly addressed its core issues. Alignment was a soft suggestion, not a hard restraint, allowing for truly good and evil people from all species both playable and monster. The setting was placed in a fantasy roughly-1920s, dealing with the lingering aftereffects of a World War and desperately praying a second one wouldn’t inevitably break out. It was noir-y, political, chock full of intrigue and murder and darkness that felt very new. And it was very popular.

Naturally there were plenty of people who weren’t excited about this setting. They didn’t like trains and airships and magic robots in their game. That’s fine, but those people are very boring.

This is the time range of the D&D website that I actually remember reading while I was playing D&D. I played a lot of Dungeons and Dragons with my high school friends, and we formed our own little “Games Club” in remembrance of a school-ordained board game after-school club that we were members of in middle school. My favorite part of the website was actually always the dice roller , which is still on the live web. I would play around with that thing for way too long for something that was just rolling dice.

August 6th, 2005

The book taking up the front page on this version is Stormwrack, a part of a series on environmental settings. This one was focused on aquatic adventures, sailing ships, deep dives, things like that. There was also Frostburn, for icy settings, Sandstorm for deserts, and so on. At this point, there would have been dozens of 3.5 Edition sourcebooks available… which, as we’ve been describing, was one of the biggest problems with Second Edition!

But this was the least of 3.5’s problems. Now it’s time to get into one of the most double-edged things about Third Edition’s life, one of the most generous actions a major company has ever made in the interest of its fans, the thing that actually saved D&D but also formed the grounds for the biggest D&D backlashes… the Open Gaming License.

Long story short, Hasbro decided to make Dungeons and Dragons open source. The core rules, stripped of anything that was not pure mechanics, was to be published for free and be usable by anybody for any reason. You could not only write your own D&D books for free, you could sell those books and make profit without having to so much as send Hasbro an e-mail. It was a revolution in gaming. The d20 System was freely available for anybody to use for anything, be it their little D&D homebrews, licensed RPGs for established fictional works like Star Wars, or completely original settings and systems for the hobbyist market. If you wanted a new RPG to play at this point, it’s very likely that your game was going to use the d20 System.

Which… is not exactly a good thing. The d20 System is fine as a game, but it’s NOT as universal as people thought it could be. Dungeons and Dragons has always been a game about dungeon crawling and combat, and trying to shoehorn its rules into a setting like Star Wars or the Wild West is doomed to fail. How exactly can you wrangle a bunch of cowpokes into a dungeon with defined monsters and treasure?

August 10th, 2006

And even then, once you’ve hacked your game to suit your Sci Fi Wild West Magipunk Dungeon Crawler With City Management Elements, you’re still wrangling with D&D’s wonky rule set. There were certain issues plain baked into the core rules that only profound hackery could resolve. The biggest of these issues was nicknamed “Linear Fighters, Quadratic Wizards”.

In a nutshell, certain classes were substantially more powerful than others, and would scale up in a dramatic fashion at higher levels. Where a regular fighter would only get better at hitting things harder and more often, wizards would gain incredible new abilities to alter the world as they saw fit. After a certain point, there was simply no way a fighter would win a one-on-one straight fight against a wizard, no matter what. The wizard could simply stop time, cast dozens of fireball spells, and walk away.

So, we’ve already gotten 3.5 Edition to repair some of the more obvious flaws, but the Linear-Quadratic issue was deep, deep baked into the game. This isn’t even getting into the “CoDzilla” issue, where a well-built Cleric or Druid could do the double-duty of a tanky fighter who can also cast powerful spells.

The Book of Nine Swords was one attempt to boost fighters up to a Wizard’s power level, but it got a very poor reception. The new classes in the book were basically Fighters But Better, and the new abilities the book provided were disliked for being too “anime”. This was on top of now the massive quantity of new source books that was in existence by this point. Yes, that’s right, Third Edition was falling into the same exact pit that Second Edition had: the rules were too obtuse, and the amount of consent available for it was too broad. No lessons were learned. Drastic changes had to be made. And there’s only one solution that’s drastic enough for Wizards.

November 2nd, 2007

NEW EDITION TIME!

This is it! It’s time to fix all of our mistakes! It’s time to have a fresh start, to renew everything, which means the cycle has to start anew! MORE playtesting, MORE media frenzy, and finally make a DEFINITIVE edition of D&D!

But this time, they’re actually going to do things different. D&D Fourth Edition was a massive overhaul. The change from Second to Third was nothing compared to this. It was finally time to ask the serious question, the one that should’ve been asked probably when the first edition was being made: What is Dungeons and Dragons ACTUALLY about, anyway?

You ask ten different people what D&D is and you’ll get ten different answers, all of them probably wrong. Many people will define it as a “role-playing game” in vague terms, describe it as a way to recreate your own Lord of the Rings-style epic story, compare it to a JRPG’s linear plotline, articulate some kind of Sci Fi Wild West Magipunk Dungeon Crawler With City Management Elements, or even try to describe an open-world sidequest-based freeform sandbox. None of these are true.

Dungeons and Dragons has its roots in wargaming, first and foremost. It was designed as a supplement to the wargame Chainmail, that allowed you to play as individual high-powered characters instead of commanding large armies of troops. This is still evident in D&D’s DNA to this day: the thing that Dungeons and Dragons is about is dungeon crawling and combat first and foremost. That isn’t to say you can’t do all of the above and more inside D&D’s constraints, but it’s like having a hammer as the only tool in your box: you sure can drive screws with it, but wouldn’t you rather have a screwdriver?

WotC, inspired by popular MMO video games of the time, streamlined D&D’s gameplay down significantly, defining character class “roles” for damage dealing, supporting, and controlling enemies. They added “powers”, abilities that reset on a timer similar to active abilities in most MMOs. They removed a good deal of the rules for roleplaying mechanics, assuming that players didn’t need to be told how to talk to NPCs.

This has to be it, right? The ultimate version of D&D. Wizards of the Coast finally went to seed, and came back out with the D&D to end all D&Ds. This is it! The definitive version!

July 2nd, 2008

Hahahahaha no, idiot.

Fourth Edition was immediately divisive. Third edition players did not like the changes to the rules - it was a little TOO much like World of Warcraft, and people accused Wizards of selling out to the video game market. They didn’t like how they gutted the rules for roleplaying. It wasn’t conducive to gameplay that WASN’T about dungeon crawling and combat, which a LOT of people played D&D for.

But to make matters worse, some of the people hurt most by Wizard’s decision to make a new edition were the independent publishers. Thanks to the Open Game License, many publishers produced their own D&D splatbooks, needing nothing more than credit given to Wizards of the Coast for their ownership of the game. Wizards declined to produce an OGL for the Fourth Edition, leaving these publishers in the lurch. Who would want to buy a splatbook for an outdated edition?

Paizo was one of the companies stuck in this dilemma. They had been producing semi-official D&D products for years and had just been given the shaft by Wizards. Well, why don’t they just make their own D&D, with blackjack and hookers and funny Futurama references? And that’s exactly what they did when they released the first edition of Pathfinder, a game that many people deemed D&D 3.75 edition.

Many people unhappy with the direction D&D was taking either pivoted to Pathfinder or simply stopped playing the game altogether. What was supposed to be a brilliant revival of D&D had become its greatest downfall in history. D&D was once again left to grope its way through the darkness towards an uncertain future… something that, perhaps, only a new edition could solve. But that won’t be well off into the future, right?

Categories: retro

Tagged: 2000 2001 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 dungeons and dragons internet archive tabletop gaming wayback machine