Frail Shells

Posted on Dec 16, 2015

Frail Shells is a first-person shooter made by Taylor Bai-Woo with music by Ryan Roth. It was released November 15, 2014 as part of the 7DFPS Jam, a collaborative game design event dedicated to making a first-person shooter in seven days.

War is hell. War has changed. War never changes. War! What is it good for? There’s a lot to be said about a good war. There is a lot to be said about a bad war, as well.

Since the world has an enormous fascination with watching people kill each other, games about war are just as prominent as real wars. Frail Shells is a game about war, but it’s not like other war games. It’s about a much more personal kind of war.

After the jump, we’ll land boots first into our review.

Note: Frail Shells is a game that’s difficult to talk about without spoiling the twist. The rest of this review contains spoilers.

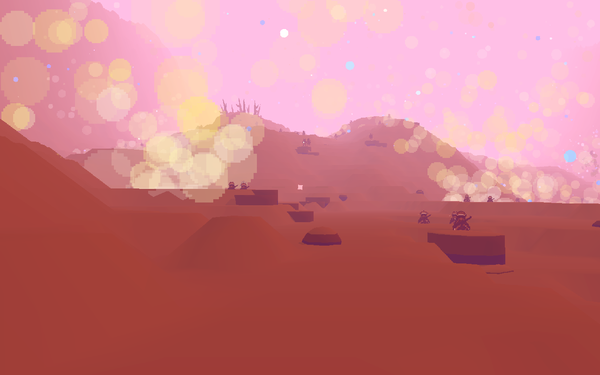

Frail Shells starts with you being dropped directly into a tremendous warzone, given a mission to rescue an allied Agent MacKenzie from behind enemy lines. You’re completely surrounded, with dozens of enemy troops firing at you. Dramatic war music thrums in your ears as your mow down enemy soldiers in quick succession with your rifle. You’re practically invincible as each enemy bullet barely scratches you, though you can die if you are totally overwhelmed.

After a while, you find Agent MacKenzie in a ditch, surrounded by corpses and still fighting her way to the last. You come close to her and she’s grateful to see you - and a bomb falls upon your location, knocking you unconscious instantly.

This is where your war story ends. But your story still has more to it.

In between scenes, you’re taken to the hospital. Your time in the war is over, and you’re sent back to your home.

You wake up in your bed, with your alarm going off. You exit your bedroom to meet MacKenzie again, standing in the kitchen and wearing an apron. She’s made you breakfast, and wishes you well on your day at work if you talk to her. When you leave the kitchen, you arrive at your job with a special lunch packed just by her. You return home every night and get some sleep. This routine repeats, day in and day out. What has happened? Was it a dream? Is the war over?

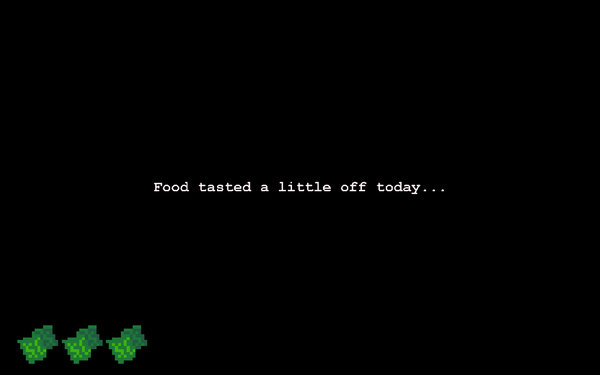

It seems like you can leave the past behind, but the war doesn’t leave you so easily. Sometimes you hear it - that pounding brass music rises up like a ghost chorus. Your gun rises up from the bottom of the screen, trying to sneak its way back into your hands. When you least expect it, you’re back there.

When your gun shows up in your hands, normal interaction is replaced with firing. This leads to obvious problems in your civilian life. Whatever you fire at is destroyed, turned grey and removed the next day. You can shoot your morning plate of eggs, you can shoot the computer monitors at your job, you can shoot your alarm clock. Nothing is safe when you have an attack. Not even MacKenzie.

This, of course, is the true heart of the game. The trauma you’ve accumulated from your war experience causes you to lash out towards the things you need in life. Every day, you must earn money to continue to survive. You accomplish this by working your job, and can earn three “dollars” a day by doing so. Talking to MacKenzie every day also rewards you with an extra dollar. Each day, you spend three of those dollars on, presumably, normal household stuff. You can only have five dollars at the most, but it’s no problem to stay afloat… for a while.

Eventually, you make mistakes. A sudden attack in the office might cause you to blow out one of your three monitors - and you earn one dollar per monitor clicked. Blow out one, you’re down to two dollars a day. You’ll still scrape by thanks to MacKenzie’s added allowance but if your gun flies into your hands while you’re talking to her, bye bye MacKenzie. If you run out of money, eventually your possessions will begin to disappear from your house until the game ends.

You might think that staying safe is as easy as being careful every day and keeping a sharp eye on when you’re going to have an attack, but it’s not that simple. The pattern of the attacks is completely random. Sometimes you might hear the music without the gun emerging; sometimes the gun will pop up before the music does; sometimes the gun will pop up so fast you’ll click before you even realize it was there. And don’t think you can keep MacKenzie safe by just not talking to her! If you ignore her, she grows unhappy and will leave you, causing you to lose her money bonus… and her sunny side up eggs.

After a while, you settle into an in-game routine. Turn off your alarm, eat your eggs, talk to MacKenzie, go to work, sleep at night. It repeats, over and over and over, for as long as you can keep the attacks at bay. You might have an accident here and there, but it’s actually very easy to stay alive overall. The real problem we had was boredom. After a while, the dull routine began to grind on our nerves. We were constantly tempted by the ever-present ability to go haywire on our surroundings, and it was only in our best interest to not do so as to keep the routine going.

Eventually, we must admit we cracked and deliberately shot MacKenzie just to see what would happen. Is this the intended end-game? After dealing with so much stress and monotony from your horribly boringly life, are you doomed to destroy everything out of bored desperation or accident? The game has no ending besides failure, as far as we could tell, and only restarted after the ending. What else can we do to survive? There is no therapy, here. There is no healing. There is only the constant, scratching urge to return to your nightmare and destroy everything you have.

After the fact…

The concept is viscerally familiar. Living with trauma in your past isn’t always something you can overcome. The feelings live on with you, sometimes fading, sometimes not, but it’ll almost always still be stuck in the back of your head. Frail Shells grasps that thin line between living a normal, dull life and snapping with a death grip.

On the art front, Frail Shells is very well made. Characters are 2D sprites with DOOM-style billboarding, and each character is well detailed and emotive. The enemy soldiers’ presumed mechanical suits of armor vent steam while they attack you, and MacKenzie’s animation is bouncy and expressive at home. The music is pulsing and triumphant, totally at odds with the otherwise domestic setting in just the right way. When you shoot things, they turn grey and flop around lifelessly like scraps of paper being thrown in the wind.

Trauma survivors are known for coping via morbid humor, so we’re going to have to admit that we got a laugh out of this game. It’s a bitter kind of laugh, and one that non-survivors aren’t in the position to understand; we received no joy from the violence, not in the same way as, say, young boys playing Doom for the first time. Still, watching the gun creep up from the side of the screen and mowing down household objects like house keys and fried eggs was just a little too ridiculous for us to not involuntarily smile at.

It’s for this reason that we were surprised to find out that all of the parallels are completely unintentional. Bai-Woo’s explanation is that the premise was just an excuse to write a game where your primary interaction with the world is shooting; she admits that she’s not comfortable with the PTSD interpretation, being someone who doesn’t have the disorder personally. We weren’t sure how to feel about this, and we were even a little bit disappointed, but it doesn’t erase the emotions it personally evoked for us.

There’s a lot to relate to, if only it had been intentional. Something that we appreciated was that, as far as we could tell, the main characters could easily be interpreted as women in a gay relationship. There’s a sock and a pair of frilly underwear on your bed; if you make MacKenzie leave for any reason (either by shooting up her house or killing her immediately), the underwear stays. Your pair of keys is pink while hers is green. These things don’t magically turn into an explicit statement, but we’d really like them to be gay. There’s a lot we’d love out of this game, but Frail Shells ultimately doesn’t make any statements about itself, which we felt was to its detriment.

Completable in half an hour: Yes

Frail Shells can be completed within ten minutes, if you’re impatient. It took us 16 minutes to beat ourselves, and that was after a dedicated effort to play for as long as possible.

War manifests itself in a lot of different ways. It’s not always as clear as two armies pointing guns at each other; a lot of the time, the biggest wars are being fought inside ourselves, against the horrors that we try so hard to keep in. We all have our wars to fight, and Frail Shells is a beautiful expose of how the pain of warfare lasts for much, much longer than the end of the battle.

Still, we have to acknowledge that all of the things we enjoy about it are personal interpretations based on our own life experiences. Devoid of context, this game is no more than a meta joke about first-person shooters; it does this well, but it’s not the reason that we enjoy it.

You can play Frail Shells for free at itch.io.

Categories: gaming

Tagged: 2014 7dfps jam first person shooter frail shells fromsmiling ptsd unity