Cuttle Scuttle

Posted on Jan 8, 2016

Cuttle Scuttle is a cuttlefish reproduction simulator by Dan Monceaux, Adam Jenkins, and Julian Shank, released on December 4, 2015.

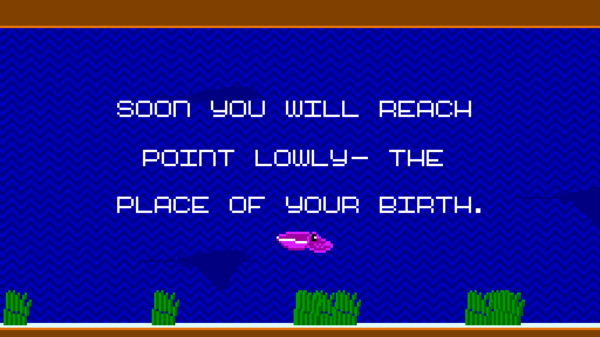

It is a companion piece to the documentary Cuttlefish Country, a film detailing the modern plight of Australian gulf cuttlefish in their attempt to survive in a human-changed ecosystem. Within Cuttle Scuttle, you play as a female cuttlefish during mating season in the Spencer Gulf. You are tasked with finding virile males to breed with, and to lay your eggs safely so the continued survival of your species is guaranteed. But it’s not easy being a cuttlefish: you’ll soon find humans are making reproduction harder than it needs to be.

Does Cuttle Scuttle successfully make cuttlefish more cuddly? Find out after the jump.

Content warnings: I don’t think any of us ever expected having to write this but there’s, uh, somewhat graphic lo-fi depictions of cephalopod sex.

Cuttle Scuttle is an arcade styled breed-'em-up with similar gameplay to a reverse Pac-Man. Instead of munching pellets, you must leave your fertilized eggs behind you. To fertilize your eggs, you must first mate with a blue-colored male cuttlefish who can also be found swimming around the map. To pass a level, you must lay 20 fertilized eggs on the screen and then you may move to the next screen.

It’s not easy, as enterprising starfish and sea urchins will be crawling around to eat your laid eggs - not to mention more voracious dolphins and fish swimming across the screen to eat you and the males. Even humans are a direct problem, with tourist divers lazily floating around, blocking your vision and making it hard to see where threats lie. To make things easier, you can consume the shrimp that also inhabit the screen to provide you with a substantial speed boost, and crabs that allow you to squirt ink to make a speedy escape.

Not even the males are interested in helping you. If two males touch each other, they’ll instigate a fight that involves the two of them flashing colorfully at each other until both run away. The males spend most of their time translucent, evidently using a cuttlefish’s innate ability to change the color of their skin to hide. You need to find uncamouflaged males if you want to mate, who aren’t too busy showing off to each other.

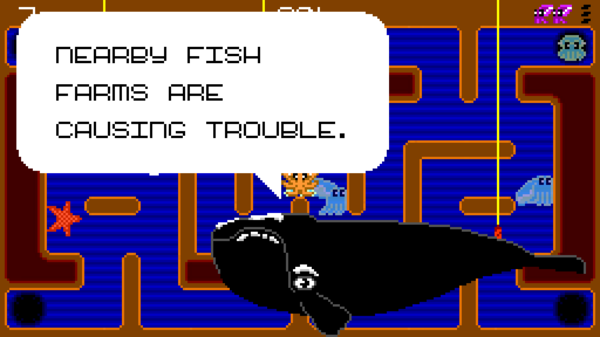

By the third level, the stakes are raised when fishermen begin to cast their lures into the waters. Touch one of the hooks and you’ll be snatched up and turned into pet food - and the same goes for the males, who are dumb as rocks and will gladly swim into a hook thinking it’s a tasty shrimp. The risks continue on each screen; on screen 6, a desalination plant is installed that causes fluctuating salinity levels that threaten your eggs. Screen 7 introduces algal blooms due to nearby fish farms contaminating the water with fish excrement.

The gameplay is solid and addictive. This wouldn’t feel out of place in a genuine old-fashioned arcade. It’s fast-paced and intense, feeling almost exactly like an old Namco game. The most interesting part of the game is that it’s actually cooperative, with up to three players working together to have a successful breeding season. This is where the game shines brightest: it’s fun with one player, but add another into the mix and it transforms into frantic yelling about “watch out for the hook!” and “oh no, I got eaten!”

Unfortunately, the franticness was partially caused by confusion about what was going on. By screen three, so much would be going on that it could become visually overwhelming to process everything. Having to keep track of males, sea urchins, dolphins swimming across the screen, fish hooks, and even more could cause us to wander directly into the mouth of a red snapper and respawn before we even knew we died.

This isn’t a problem in its own: we like chaos in games, and it can be fun. That said, a lot of it just seemed to come down to mistakes in design and color weighting. The color choices felt random at times, which is a typical by-product of games trying to look retro; real retro games, having less colors to choose from, had to manage their color budget and make everything display distinctly on the screen. With the opportunity to make all the sprites clear and bright, everything on the screen fights for dominance over your attention.

Here’s some clear examples: in the multiplayer mode, the second player is colored green - a shade of green that is very close to the blue males. The first player’s pink is perfectly visible against everything else, so why not player two’s? Deadly snappers being the same color as non-deadly starfish was also a direct contributor to making game-losing mistakes, especially when the shrimp power-up is in play.

Speaking of pink, we weren’t particularly impressed that the default player is pink while the men are blue. It’s quick visual shorthand, and it’s not particularly dealbreaking, but if you go to the title screen, the single-player character is shown to be green; yet, when you select her, you’re given the pink protagonist instead. Cuttlefish come in all varieties of colors, so it feels unnecessarily constricted.

The most confusing bit was that a large majority of options were actually turned off at the beginning of the game, namely all audio and a friendly whale that explains new concepts to you. We were very, very confused when the game opened without any sound at all and were ready to chalk it up to a glitch before we found the options menu. Having the whale disabled at first makes no sense either - admittedly, their enormous bulk does cover up a large part of the screen during their tutorial bits, but they provide more helpful info than they hinder. It would’ve been nicer if they swam off screen faster, though.

Even with the tutorial whale, some things were just plain not explained at all. We didn’t know at first that you had to eat a crab to squirt ink, and were befuddled when hitting the ink key did nothing. The rules of the game, in general, weren’t explained very well - we had to work out ourselves that when the males began to flash, they couldn’t be mated with, and also that starfish and sea urchins destroyed our eggs. We had to figure out all of the rules ourselves. This is something that we normally consider to be a selling point in games, but since the game gives you no time to figure out what’s going on, it would’ve been nice to have an instruction manual.

Some points of the game even seemed glitched. Sometimes we were eaten by fish or dolphins immediately post-coitus with a male in ways that didn’t make sense - did the size of the mating sprite causing them to collide with us, making them eat us despite being further to the right or left than felt right? The same thing would also happen with fishing hooks, causing us to get snatched by a hook that was directly to our side.

On the audio and visual side of things, Cuttle Scuttle perfectly imitates a classic vintage feel. The music is excellent, and frames the mood of the game in its tone. The music in the first few levels is bright and buoyant, and becomes progressively more and more industrial as human interference progresses into the world of Point Lowly. When you eat a shrimp power-up the music changes to a throbbing high-speed melody that keeps the mood speedy while you zip around under the influence.

After the fact…

Cuttle Scuttle is a political game at heart, and presents a very clear message: cuttlefish are suffering on the south Australian coast, and human interference is a direct threat to their life cycle. It’s surprisingly emotional to think about the things that these humble cuttlefish to through just to stay alive, and having your score streak cut short by an errant fishing hook must feel like nothing compared to an actual cuttlefish having their life ended. The game gets the feeling of the cuttlefish struggle across with aplomb, wrapping what would be an otherwise overlooked situation up into a tight, attractive, retro-styled package. We definitely learned a lot about what cuttlefish feel from this game.

Once you’ve lost all three lives, you’re given a final tally of two scores: one of how many total eggs you laid, and one of how many managed to make it to hatching. It’s mildly distressing to see how many eggs are lost during the course of the game, but also heartening to see just how many cuttlefish babies are born from a single parent. Good luck on those hatchlings to survive to next breeding season, though.

Cuttlefish Country (the documentary this game is based off of) has yet to be released, but we hope it will succeed in raising awareness of cuttlefish suffering. Cephalopods are some of our favorite animals in the world, and cuttlefish are so uniquely precious to the world it would be abominable to allow them to go extinct.

Cuttle Scuttle is tightly woven and carries a strong message, but a few loose threads around the edges keep it from being perfect. The gameplay is tight, if not very difficult, but a bevy of confusion turned fun franticness into frustration. This game is still in beta release, and we hope will get progressively more polished by the time Cuttlefish Country comes out.

Cuttle Scuttle can be purchased for $2.99 on itch.io.

Categories: gaming

Tagged: 2015 adam jenkins arcade game cuttle scuttle dan monceaux female protagonist gender julian shank